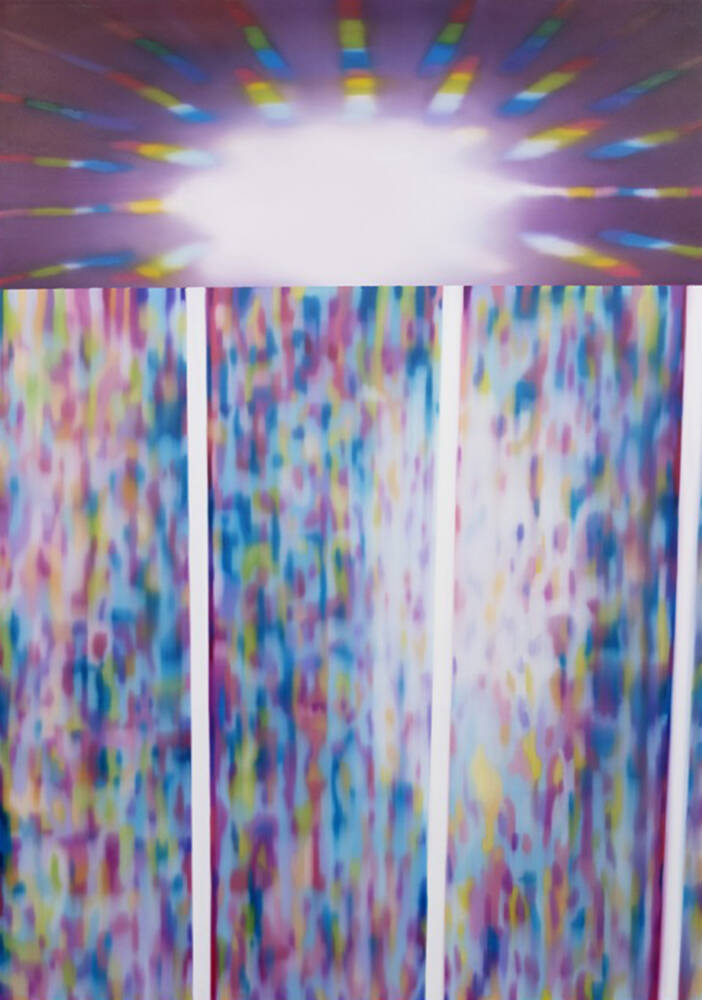

Reality is always deeper, larger, more profound and crazy than we can comprehend

In this conversation, the artist Robert Roest offers insight into his complex body of work, creative processes, how he deals with doubt and why he uses microsoft word to work with images

A good start into our conversation is your series “indoor feelings and single-door kennels to your soul”, because that’s how we got to know your work. The images show portraits of domesticated and tamed breeding dogs, in a state of defense, gnashing their teeth.

These paintings are not dog portraits, they’re not so much about the dogs themselves. My work is always about humans, even when I paint dogs. Everything I create revolves around issues of perception, projection, interpretation, deception and illusion. Our senses are not a transparent window to reality, but a filter which leaves most of it out. The dogs I painted look very aggressive, almost demonic, but most likely they’re just yawning, or barking with curiosity and there’s nothing evil or scary about them: it’s purely appearance. I imagine them being very kind and sweet creatures, only captured in a moment looking their worst. But it’s completely deceptive: technological flaws or failures, trying to capture reality.

Could you elaborate a bit on the title you chose for the series?

A title is always like making a painting. Most of the time they don’t come easy to me, but they are very important to me. I can’t exactly remember how I came up with this one, its an intuitive title.

Every series is accompanied with a text by me — the title and the text are almost like the other side of the artwork — like the other side of the same coin.

How are you attached to your pieces? Are you more attached to certain pieces, than to others?

The paintings I feel most attached to, are often those which are technically executed the best.

Do you see the whole work is always the complete series or how would you differentiate the single image and the whole series?

The single painting of a series can stand on its own. However, I work in series to make my artistic practice coherent. Like a song, which relates to a whole album: some people only listen to the singles they like best, but it’s still always part of a whole album.

You can look at a painting as a single, but it’s meant as a whole album. That’s the best way to describe it.

From what I read in your texts, technology and the digital realm are always important parts of your creative process. What steps do you take before starting to paint?

The digital medium I use most is microsoft word, because I’ve never been really good at photoshop, I’ve never bothered to learn it. I work with screenshots from the computer, found footage or my own photographs and combine them in collages. Microsoft word is mainly for working with text, but there are some basic image editing tools like resizing, cropping and mirroring. Its its very unsophisticated, but the solutions I find later on, in painting.

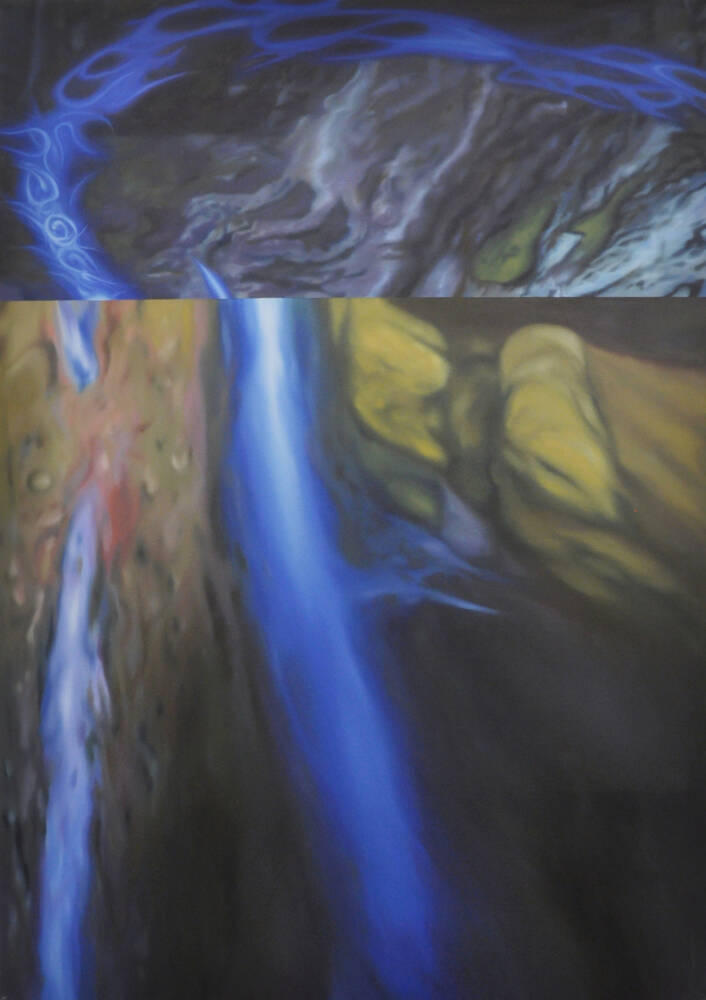

In “Fueling flames, don’t worship ashes!” you drew on a touchscreen and then deepened the process with painting. How did you experience this process?

It’s my most abstract series, I call them touchscreenpaintings. Drawing with my fingers on my phone was a very primitive way to draw. But that was exactly what I liked about it. I first started just playing around with it and then I started to like the fight with it. It was like a wrestling with the medium.

That’s similar to the limitation by using microsoft word to edit images.

I search for limitations in my work. The subject of a series is also a limitation.

But within the whole of my work, almost everything is possible. I like the limitations of microsoft word or the limitations of samsung notes. The digital is always present in my work, even though I’m not very knowledgeable about it. Maybe that’s why it works for me. Because, when you bump against some limitations, and you have to work with it to find solutions, it makes you more inventive.

Would you say limitation is something like a challenge for yourself? Having to find a solution for the limitation and overcome it?

It’s also a protection, because limitation is the very reason we survive in the world.

If our mind would let everything in, that’s possible to experience in the world, we would become completely dysfunctional. Maybe its more of a help than something that needs to be overcome. It’s more of a tool.

In your own words, what is your work about?

The world is such a complex place and we should try to postpone our judgement about things, a little bit. Because we have a very warped and limited sense of what reality is, we’re quick to interpret and have an opinion about something, but my work tries to deceive.

Reality is always deeper, larger, more profound, more crazy than we can comprehend. Hence, what comes in — be it through vision or any of our senses— is always just a fragment of reality. What we think we know about the world or about reality is extremely limited, and also skewed by us, which makes us biased as humans.

So you aim to create a little crack in the observer to let something else in?

Yes. It would be helpful, and maybe result in a more kind and understanding society, if more people realized that what they think, is not the world. Oftentimes, it’s a little more complex, a little bit more nuanced or even completely different — and its’ no problem. That is a very moralistic interpretation of my work maybe, but it is somewhere around that.

What are your thoughts on the growing need for artists to market themselves? It’s more and more important to present yourself on social media.

Mostly, I’m happy with instagram, because it exposes my work to such a wide audience. Of course, it’s not immediately, the audience grows over time, and you have to be a little bit lucky with the algorithm – something I really don’t understand. Some paintings have a lot of views and other paintings, that I think are better, have less exposure.

Do you have any role models?

It’s a fictional character: the detective in Twin Peaks, Mr. Cooper. He looks at the world with curiosity, an openness and a matured childishness. Lots of people stop being childish and loose their curiosity and become a little narrow-minded. Dale Cooper is such a wholesome person. He is not scared. He exposes himself also to the dark sides of life: crimes and horrible stuff, without breaking from that. He can be sad about things and mourn — he’s not indifferent at all – but still it doesn’t crack his love for life and his kindness for people.

So, the nonplus-ultra would be agent dale Cooper, appreciating one of your paintings? Or is he more like a role model to you personally, all art aside?

Yes, as a human being, but also as an artist: his whole non-judgmental attitude towards the world. Also, the philosopher Nietzsche has always been influential to me. His writing style, the variety of topics he covered and his ability to see things from many different angles.

A broad horizon of perspective is immanent in your work and makes each series quite different. What, would you say, ties them all together?

The reflection on the interrelationship between reality — senses — mind. I’m interested in the impact images have on us, and the impact we have on images. Because, even if an image doesn’t visually change, our ways of seeing do change. I guess the foundation for all my work is curiosity and open-mindedness. I allow myself to get exposed to diverse opinions and approaches. I don’t just dispose of opposing views, but take them seriously and with some curiosity think “oh this is also a way of think about it.”.

Not to know everything — to be fully okay with the mystery of life.

Rest in that.

Ok, that is the philosophy underlying your work. But more specifically, how do you explain the visual differences from series to series?

When I graduated from art academy, I had many ideas for projects I wanted to do. However, I didn’t gravitate to one particular style. Rather, I wanted to find a way to explore all of those seemingly contradicting approaches — minimalist and complex, figurative and abstract, wild and calm, cheesy and serious. To incorporate all of this, I decided to work in series.

In your artist statement, you write that your work is rooted both in the contemporary world of new media — hence the research, the collages — and the history of painting.

I feel drawn to old art because its so beautifully and well done and I feel so much emotional power within it. The avant-garde movements after the 1930’s taught me a lot as well.

Balance is important to me: technical, traditional perfection but contemporary ideas. I’m not interested in a perfectly painted image without a subject that makes me curious. Boring but beautiful is not what art is about — to me. I’m trying to get the best of both worlds: a symbiosis of academic, traditional painting-techniques and contemporary subjects.

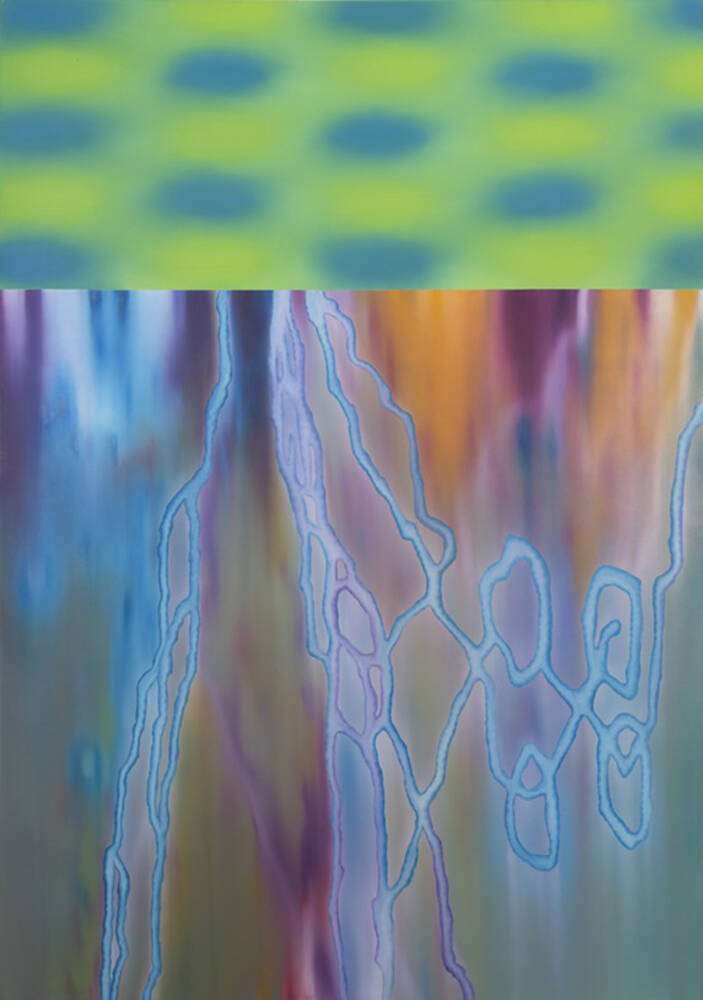

This makes me think of your “Meatware Ecosystem”. These pieces are symbiotically both: digital and technically traditional at the same time, wouldn’t you say?

Those paintings are based on computer games. I imagined being an artist living in a ceratain game. So, this game world was the only world I knew — I imagined it with totally different art history, ridding myself of all the impressions and presumptions I had in real life. These paintings are between abstraction and figuration. You see certain forms, but you don’t really know what you’re looking at.

Already at an early age you were good at drawing and painting. Would you say that studying at art academy was still a necessity on your path to becoming an artist?

Totally. I could technically paint and draw pretty good — copying Rembrandts for example — but I knew that art making had to do with creating something new, original.

During art academy, I unlocked my creativity. Prior to moving to Utrecht to study, I grew up in a christian community. My exposure to culture, music, film and literature had been very limited. So, at 17, all of those worlds and possibilities I wasn’t even aware of, opened up to me. It was one big feast for me. I had a really good time.

Would you say, having graduated from art academy was kind of a ticket into the art world? That you’d be perceived differently if you didn’t?

No, it didn’t really feel like a ticket into anything. It did open up my world and I learned a lot of things, like how to start a process, how to artistically keep it going and grow and expand and deepen. But all of the practical aspects, like how to survive as an artist or how to get into a gallery, how to do exhibitions all that sort of stuff — that grew over time quite slowly, kind of learning by doing.

So, is art education overrated and no longer relevant?

Although I’m convinced one can be successful without traditional art education, I do think it is still very important for many reasons. If you’re self-taught, your world is often narrowed to your own taste and preference. At art academy you come in contact with things you probably wouldn’t come up with by yourself. Learning to grow from criticism and input from various teachers and students is very valuable. Having to talk about other people’s work — it’s difficult to organize things like that on your own, outside a proper art education. But of course, there are also many exceptions to be found.

How do you deal with doubt? Do you have certain things that you do when the doubt is coming?

There are various kinds of doubt. One is the technical doubt — where the concept works, but I’m unhappy with the quality of my painting. With the paintings I’m currently working on, I was close to taking a loss and acknowledging that I am not capable of technically make it good enough.

Before abandoning the series, I went to the MET to look at some old masters. I realized those big masters, who painted those really well done paintings, had had the same muscles in their fingers, the same arms and the same brain as me. They just knew something I didn’t. Later, I fortunately met an academically trained painter who taught me some tricks — physically not hard to do, but someone just needed to show me before I could apply it.

Aside from technical doubt, what doubt do you experience?

Every time I finish a series, there’s this moment of doubt, when I have to start from scratch. I work at one series for about a year or longer and really dive into it. Once it’s done, I want to reinvent myself, which can result in a doubting period where I’m afraid that I won’t have any good ideas. But until now, it has always continued.

Regarding ideas: do you always first have a vision in your head, then do the collages and lastly, paint?

It depends on the series. Sometimes it starts with an idea and sometimes with already worked out pictures in my mind which I then have to execute.

At the start of any project is my awareness, having my senses and mind open and letting things come in. Then, I kind of just trust the process. Whatever stays or resonates with me or fascinates me for some reason, I pursue.

Image credits: © Robert Roest

Cover: © André Smits