Artist Clara Bahlsen shares her thoughts on the pleasure of images, the bliss of teaching and the power of community

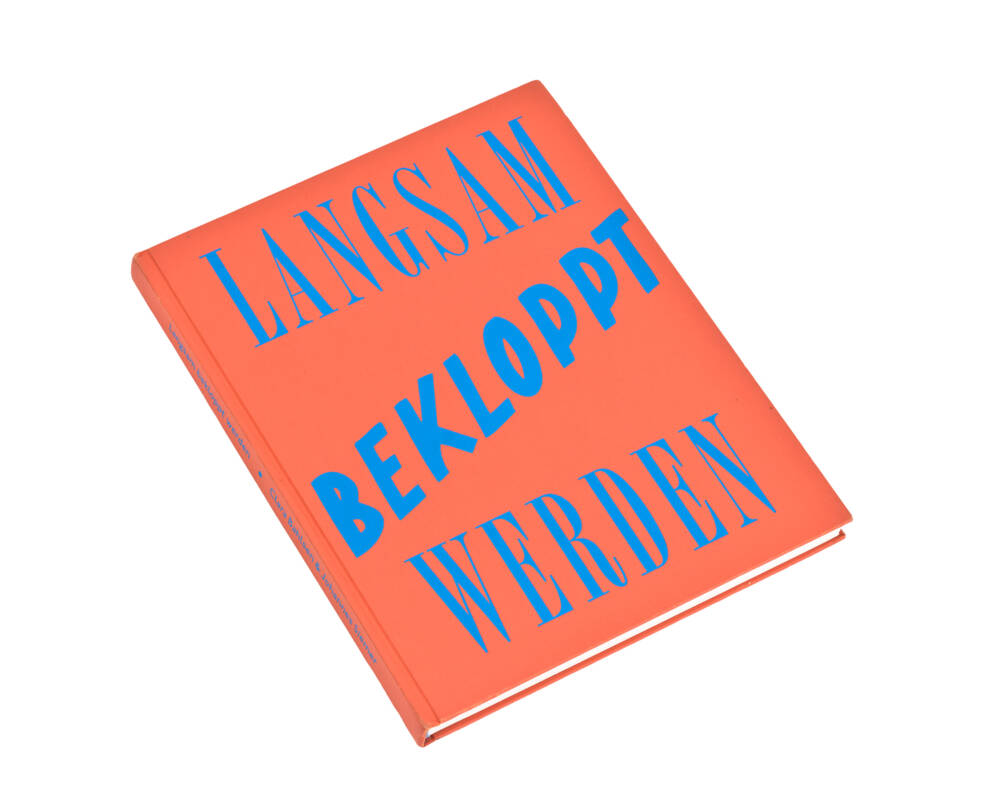

With a background of visual communication and photography, Clara merges installation, text and photography in her body of work. After meeting at the Book Days during Foto Wien earlier this year, we had a conversation about self publishing, creative processes and the value of embracing unconventional paths

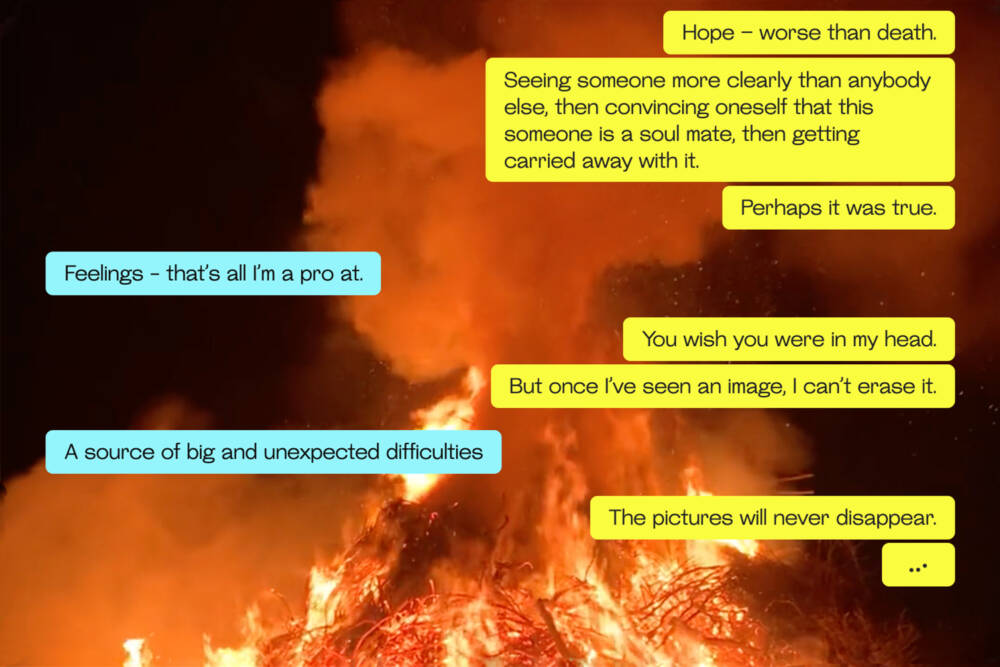

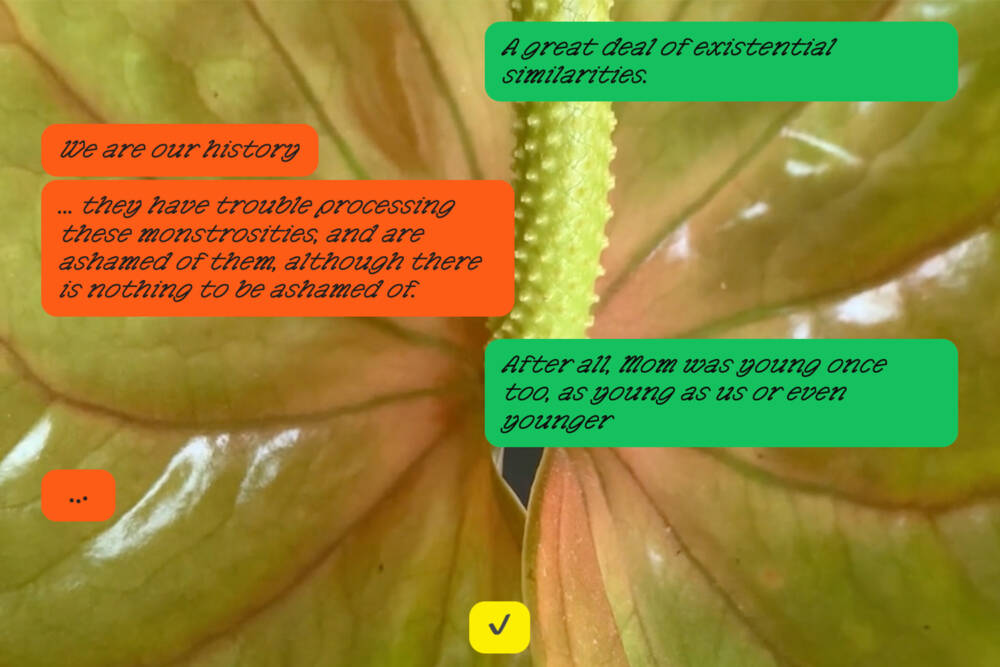

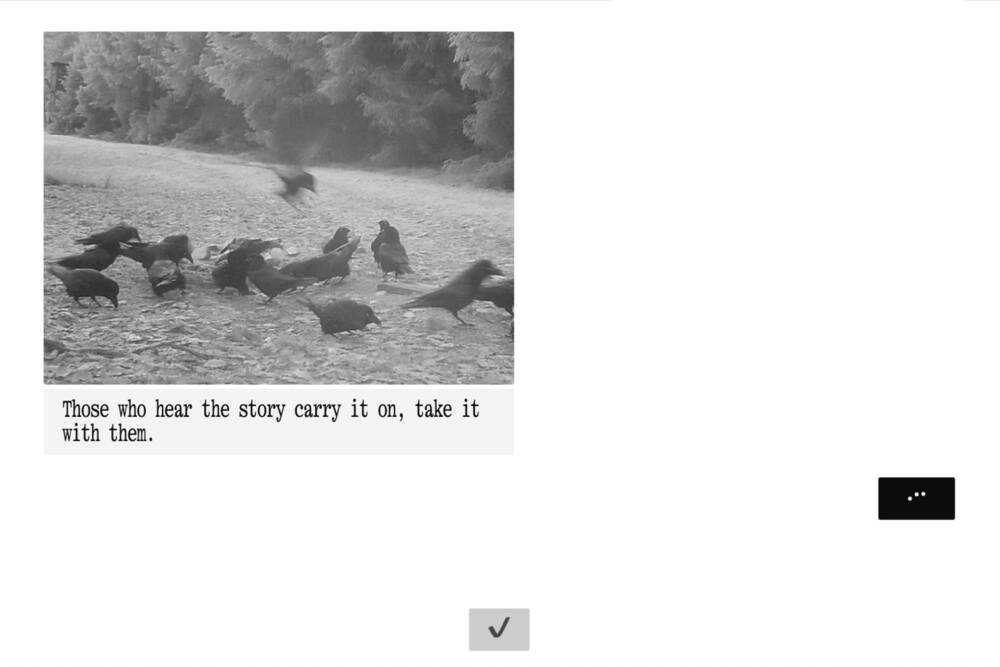

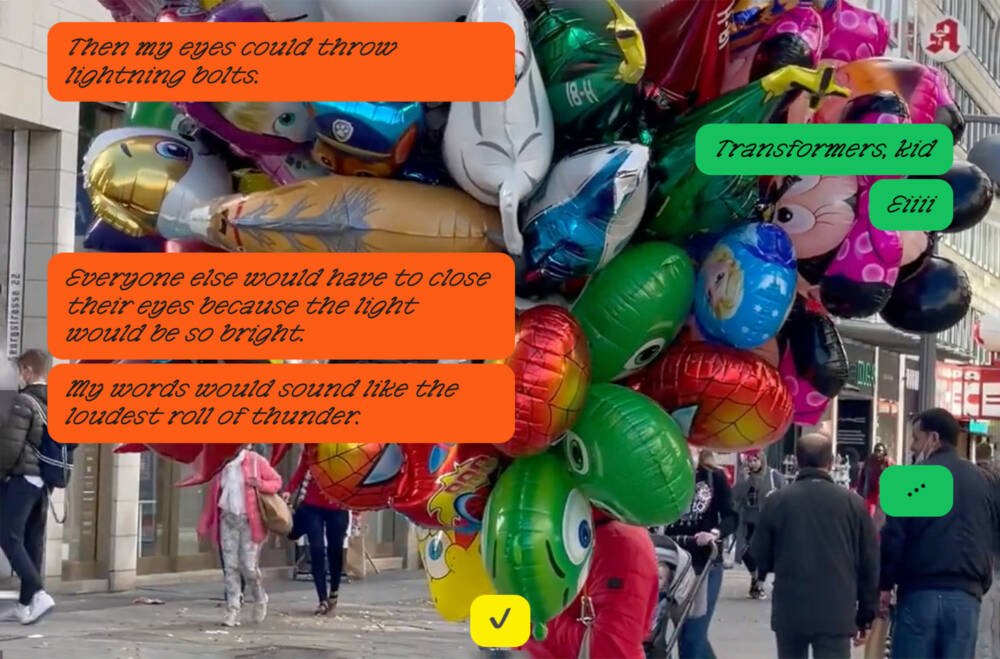

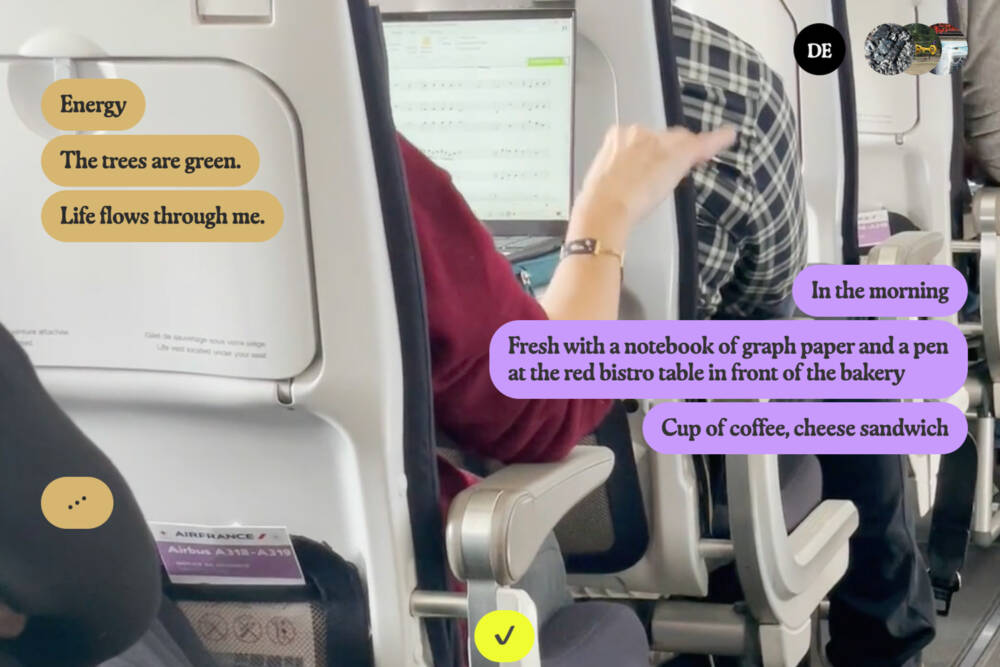

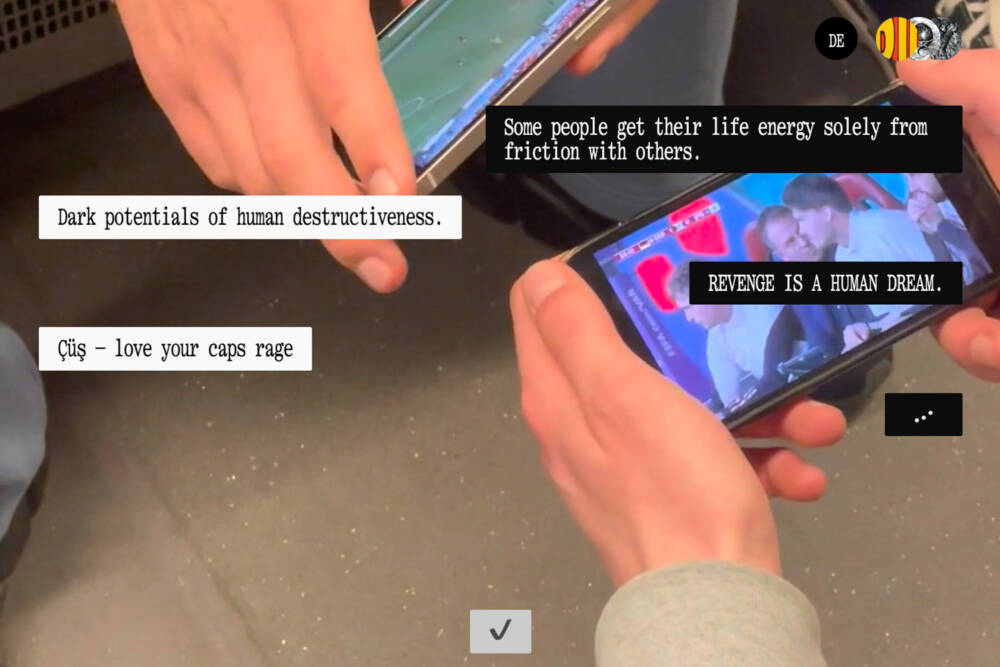

Your most recent, ongoing project, ”Welcome to Human Club” (WTHC) is a digital publication, yet it is not an eBook or a PDF, but an interactive book. In an all too familiar chat format, the text is being displayed in form of a conversation with a background of changing videos and images. In a way, one feels like reading someones conversation over their shoulder as it happens. I couldn’t help but feel like I was looking at something not meant for my eyes. Did you intentionally create that element of voyeurism?

I spent a considerable amount of time contemplating what a digital publication could look like, striving to find a digital equivalent to a physical book. The chat format resonated with me the most in this regard. We have all become so instinctively familiar with it in the digital realm, much like we are with printed content. The voyeuristic element intrigued me deeply.

When I read a book alone, I also experience a sense of privacy or intimacy. However, it’s essential to recognize that a book, in most cases, is produced in large print runs, so my personal moment of reading is simultaneously a communal one. Similarly, chats that occur between two individuals carry a similar feeling of privacy. I enjoy playing with the expectation that the chat in “Welcome to Human Club” (WTHC) contains private content that the viewer can read. However, the chat text is, of course, carefully curated and not actually private. It follows a predetermined linear sequence, with the user controlling its progression through a CTA button, similar to turning pages in a book.

During my work on WTHC, I often pondered whether it would be interesting to have an app that allows individuals to make specific chats public on their own phones. Users could then read chat conversations of strangers within the app, or I could make my own chat publicly accessible, knowing that others are currently reading it. This concept explores the intersection of privacy, voyeurism, and digital interaction in an engaging way.

Do you think this voyeuristic taste is absent in reading a printed dialogue?

I don’t believe that the voyeuristic element is entirely absent when reading printed dialogues. There’s a natural curiosity about life, both our own and the lives of others. Reading other people’s diaries or letters is a common scene in films or stories: Parents read diaries of their teenage children, spouses read love letters that are not meant for them, etc. However, when a person passes away, their loved ones often read their diary because the curiosity is too strong to leave it in its private state. So, in essence, the voyeuristic inclination exists in both digital and print formats; it’s a fundamental aspect of human curiosity about others’ lives.

The fonts and colors vary from chapter to chapter in WTHC. Why and how did you decide for a font? How do images, words and fonts influence each other?

The chapters in WTHC are a fusion of text, image, video, and rhythm. Videos serve as surfaces where text expands, supports, or extends, creating a symbiotic relationship between the two. Tension and engagement arise from this coexistence. Each chapter has its own appearance: bubble shape, font, colors. It should look like a new volume of a book series, so that connections are recognizable, but at the same time a new chapter.

Text creation mirrors my approach to photography: I capture sentences, read texts, extract phrases and words from conversations. Sometimes it’s immediate transcription, while other times, thoughts, ideas, or feelings are later crafted into text. Reflection occurs as I sift through my collected material, leading to the writing of a new chapter.

In general, could you elaborate on your inspiration to WTHC? How many more chapters are planned?

Initially, I envisioned six chapters, the 6th chapter is confirmed for this year. Now, I’m considering the possibility of extending the project even further. There might be additional chapters that could be available for purchase or tailored for specific individuals. I’m also exploring collaborative opportunities to develop new chapters with other people, as I have many ideas in mind. So, the project’s future is open-ended and I am curious myself.

After your studies of visual communication with Fons Hickmann at University of the Arts Berlin and your post graduation with Ute Mahler & Robert Lyons at Berlins Ostkreuz School of Photography, you started teaching yourself. What motivated you to make this decision?

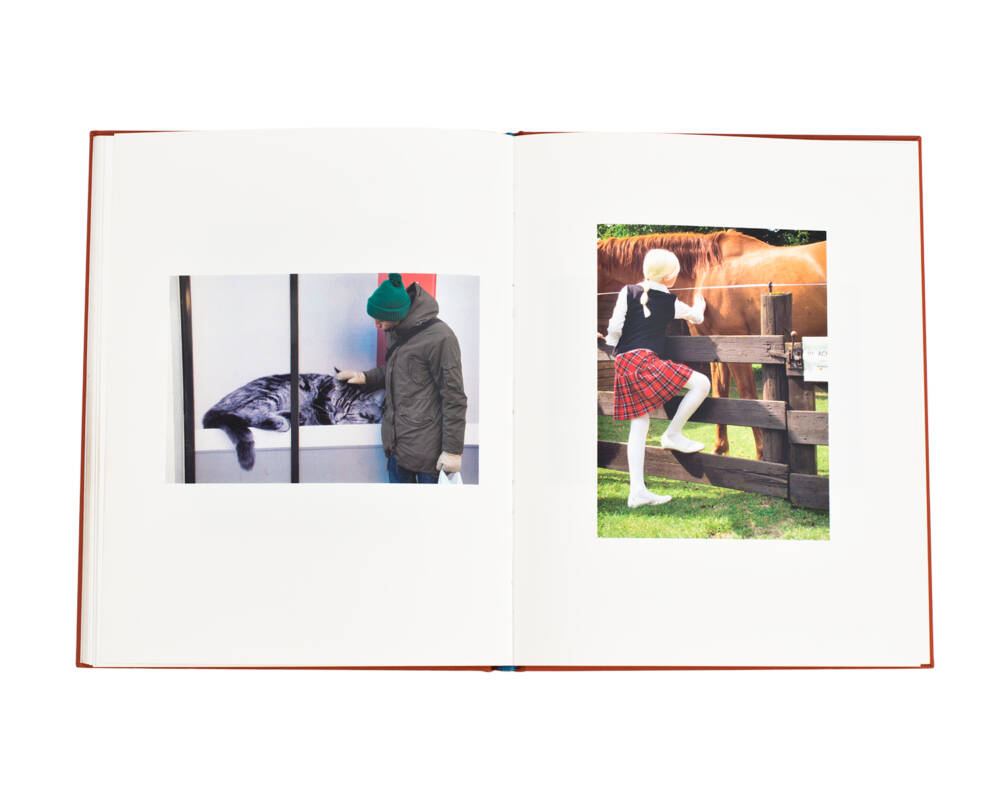

What I enjoy most is the process of editing images. This passion dates back to my studies and has become one of my greatest strengths. Over the years I’ve had the privilege of working with various artists and photographers, selecting images and refining sequences for photo books and exhibitions. In particular, last year Prof. Wiebke Loeper approached me with the opportunity to teach a photo book class at the Potsdam University of Applied Sciences. To put it that way, this role is a dream job for me. It involves the pleasure of looking at compelling images together on a weekly basis, engaging in discussions about books, and witnessing the evolution of a new publication from a strong series of images – it’s sheer bliss!

Why did you study visual communication in the first place?

I chose to study visual communication because of my deep-seated fascination with the power of visual storytelling and communication. From a young age, I was captivated by images and photography.

Would you say, at some point you knew photography would be the predominant medium to work in? If so, why?

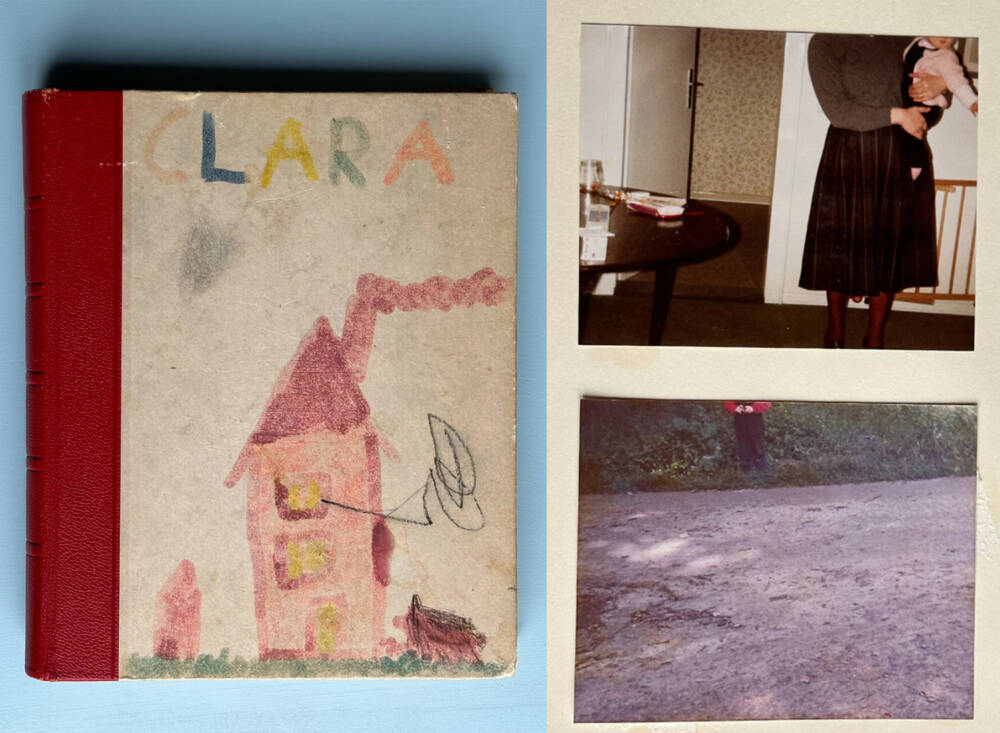

I got my first camera when I was about seven years old and made a book of the photos I took. I still have the book. There are two pictures in the book that I still like: one is of my mother holding my little sister and the other is of my little brother: all of them are missing their heads. These photographs very accurately describe my situation as the eldest sister, looking enviously at the younger siblings who had abruptly ended my era as an only child.

When I was a teenager I got my first SLR camera and shortly afterwards I learnt to develop my own black and white pictures. A friend of mine had a lot of photo books and I could hardly believe my luck when I realized it’ possible to make books with only photographs. As a young child I had a few children’s books that were based on photographs rather than illustrations. Those books were like a treasure and I still remember the pictures.

Eventhough I may not have known it at that time, these experiences and my growing fascination with photography gradually led me to realize it would become the dominant medium. Photography’s ability to communicate without the need for words and its power to evoke deep emotions became increasingly evident to me, solidifying my path as a photographer and visual storyteller.

How do graphic design, Typography, Design and photography correlate in your work overall?

Connections – I am interested in different disciplines, their connections and in-between areas. I studied visual communication but work as a freelance artist. I have published artist’s books, now publish digital formats. My artistic work has a photographic focus, meanwhile it is mainly installative, to name just a few examples.

Is there something you would wish to do differently than your own studies-experiences? Something you really enjoyed and want to pass on to your students?

One important lesson I’d like to share with my students is the value of embracing unconventional paths. While I didn’t formally study Fine Arts or Photography, I believe that this unique journey allowed me to discover my passion for creating books, which has become a central part of my creative work. It’s a reminder that sometimes, unconventional routes can lead to a clearer understanding of one’s passions and strengths.

The medium of the printed book is dominant in your body of work. Could you elaborate on the meaning of this medium?

The fascination with storytelling and its diverse techniques has always held my enduring interest. Stories, fundamentally, provide depth and significance to our existence. My curiosity centers around exploring the boundaries of traditional storytelling and experimenting with established forms.

Books, as a medium, attract me for their inherent “limitations.” These constraints offer a significant creative challenge that I eagerly embrace. At the same time, I let go of complete control over where and how the book is experienced, leading to a sense of ambiguity and unpredictability.

You exhibit your work on a regular basis, how is the installation different to a book? Would you say the book is a mere documentation of the exhibition or work of its own?

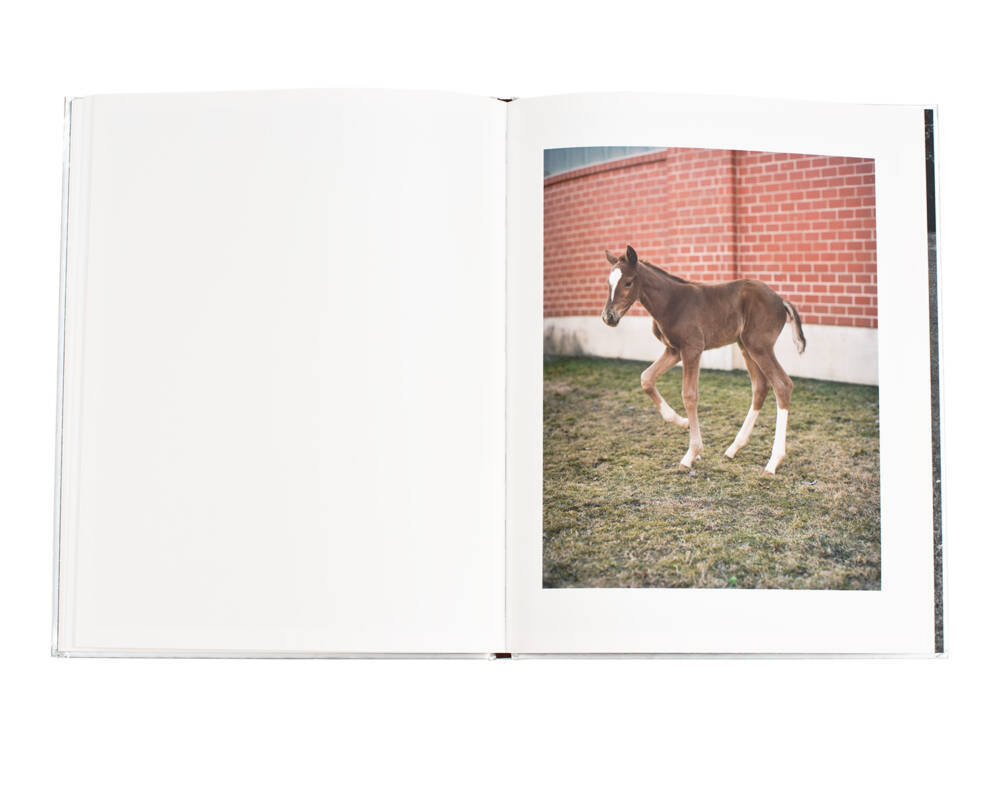

In my perspective, books are artistic works in themselves. When I exhibit the same images, their spatial arrangement is entirely different from the sequence of images in the book. The way stories function within an installation differs notably from their presentation in a book. It’s this contrast, that strongly appeals to me.

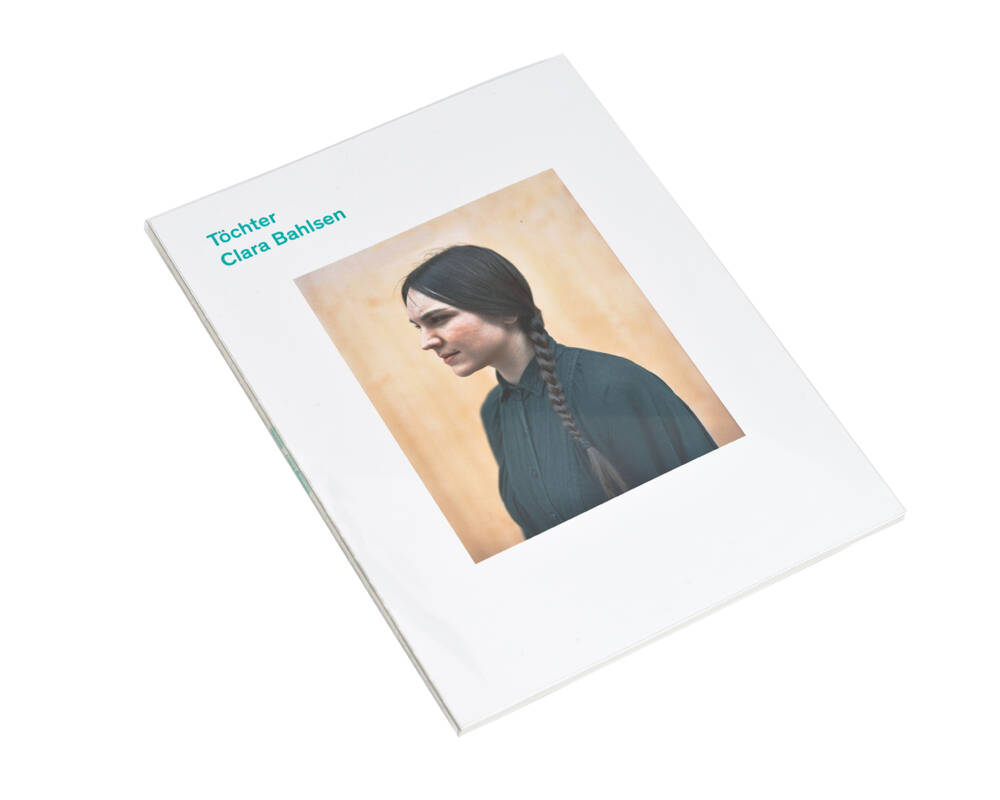

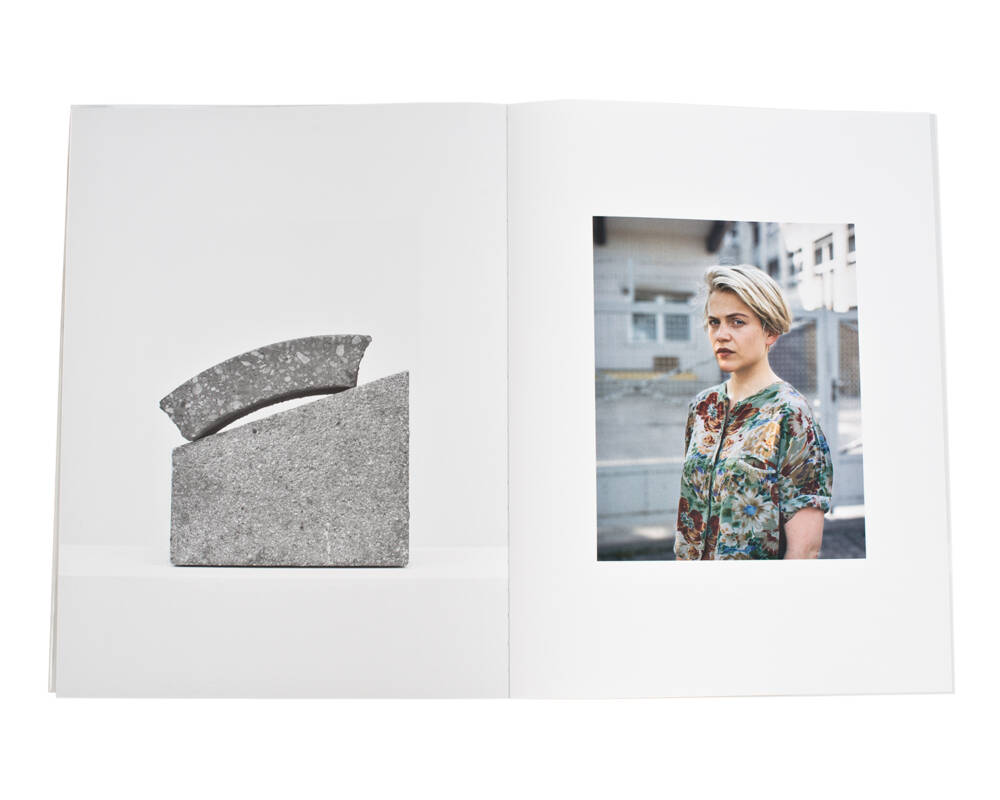

For example, in the book “Töchter,” the stone sculptures I refer to as “houses” are often presented on double-page spreads, essentially paired with the portraits. This sequence and arrangement take on a different form in a physical space because it allows for the simultaneous viewing of multiple images. The portraits are presented framed in the room. The stone sculptures are printed on wallpaper and glued directly to the wall of the exhibition space.

The portrait always reappears in your work. What does the photographic portrait mean to you, personally?

When I photograph a portrait, it’s about relationships. It’s not just the person in front of the camera; it’s also about my presence in that moment. We both share this common situation, and I’m simultaneously observing and recording it through the camera. We share time, attention and negotiate the question of what exchange we can enter into with each other. I am very grateful to the people who engage in this special exchange with me.

Except of your publication “1-500”, you published your books on your own. Could you tell us a bit about your experiences with self publishing?What are the pros and cons?

I greatly value the creative freedom that comes with self-publishing, allowing me to design a book precisely as I envision it, without the constraints imposed by external parties. However, it’s essential to acknowledge that self-publishing involves a substantial amount of work in various aspects, which I initially underestimated. One significant challenge is distribution, which can be complex and demanding.

Do you plan to share your expertise of publishing with collaborators? do you have a plan to open up a publishing house?

I’m always open to the possibility of collaborating with a publishing house for specific projects. Additionally, if someone has exceptional images and is in need of assistance with the editing process, I’d be interested in exploring such opportunities. So, please don’t hesitate to reach out if you have compelling work to share.

Talking about collaborations: I have been running an online archive since 2006, which started as a fun hobby and has since grown. By today it’s the largest collection of images of anthropomorphic objects that I know of. Have a look at www.yspisfy.com

Some of your projects are sculptural (Wand, Palette/Pfeiler, Show me first). Would you say, the 2 dimensional quality of photographs is too limiting to express what you want to say with your work sometimes?

For a long time I made sculptures and then photographed them, presenting only the photographs in exhibitions. In these cases, the photograph itself was the final artwork. Gradually, however, my practice expanded to include the third dimension within physical space. I can’t pinpoint the exact development of this shift; rather, it was a path that I naturally continued to explore.

Another factor that may have contributed to this transition is my innate curiosity and wide range of interests. I tend to get bored quickly, so I am always involved in several projects at once. Interestingly, I’ve found that boredom can be an important source of inspiration. Some of my best ideas have come from moments of deep boredom. You could say that boredom acts as a unique muse in my creative process.

Artistic practice comes — to most — with (self) doubt. In case this applies also to you, how do you deal with it?

Artistic practice often involves self-doubt, and I’m no exception. The main difference between my early days and now is that I’ve come to understand that doubt is a natural part of the creative process. I know that doubts come and go, and I’ve learned to accept them as part of the journey. This sense of certainty about the transient nature of doubt is something I didn’t have at the beginning, and it has made dealing with self-doubt easier over time.

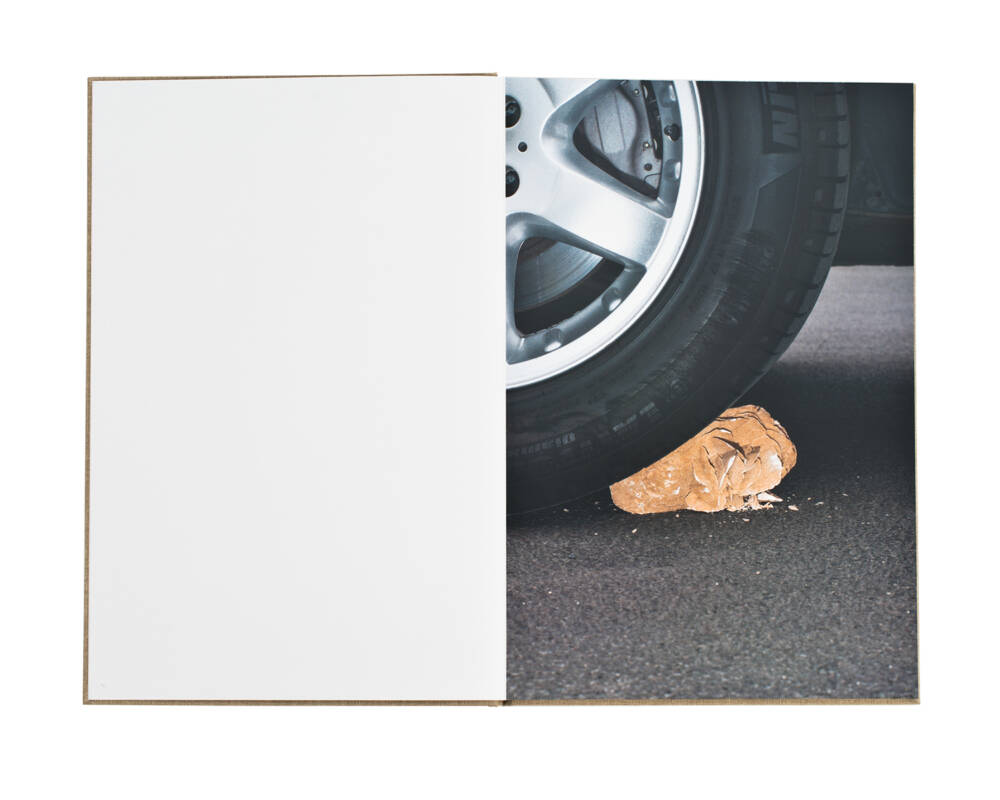

The organic and the inorganic seem to be in dialog a lot of the time in your work. Zement, Magical Rage and Graben, to name a few projects, very strongly contrast the artificial and the natural, making the viewer weigh the difference of these states. How would you describe this correlation in your own words?

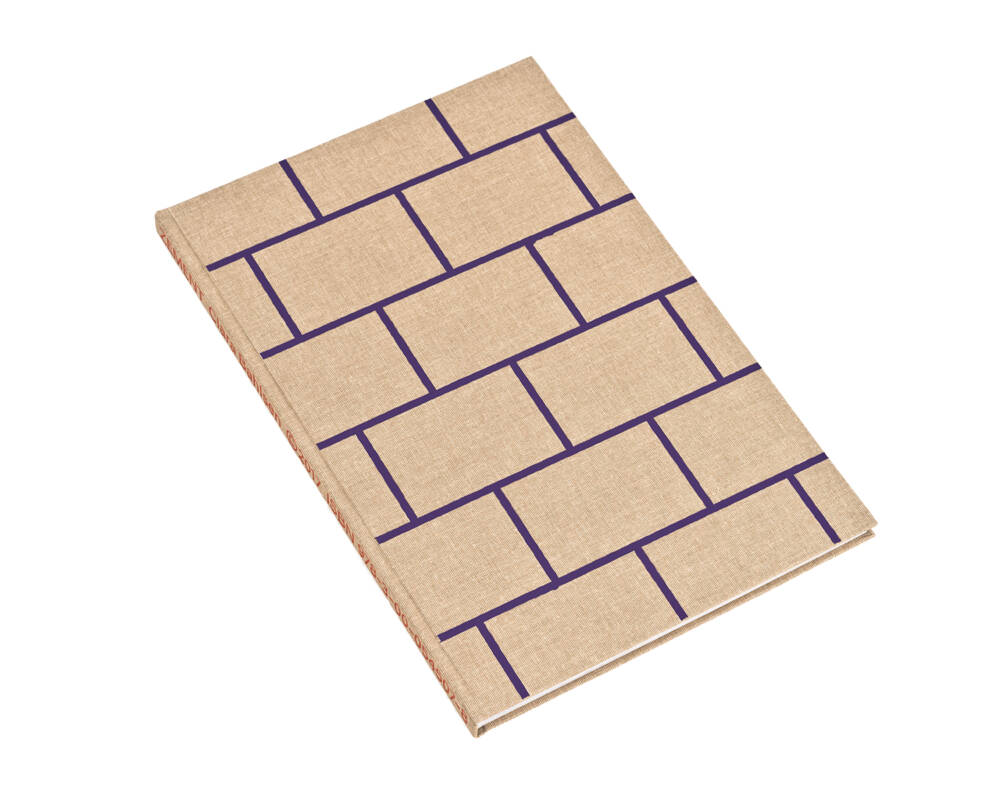

I am fascinated by materials, surfaces and objects of all kinds. All objects have a story. I’m curious about playing with these stories through photographic images, taking them away, changing the context or writing a new one. There are certain surfaces, like bricks, brick walls and stones in general, that keep coming back to me in my work. I don’t know why, but I suppose it has something to do with the rural area of northern Germany where I grew up.

Sometimes it takes me ages to find the right combination of objects and materials for a photograph. Often the objects elude me and the camera, then I try again and again until I find out how the things show their energy or peculiarity. For me, photographing objects is similar to photographing portraits: it’s about connections, relationships, when I take it to a very abstract level.

How do you personally shift between digital and analog?

For me, shifting between digital and analog photography is a matter of concentration and contemplation. When I photograph digitally, I do so without much thought, and the real thinking process begins when I review the images. In contrast, when I shoot analog, I engage in thinking both before and during the process of taking the photograph. The analog medium requires a more deliberate and mindful approach from the outset.

What is the most treasured advice you have received?

The most valuable advice I received was to remain open to experimentation and exploration in my creative practice and not to judge the work and anything that comes out of it too harshly at an early stage. Moving on is definitely much more important than judging everything all the time.

Any advice you give to young, emerging designers/artists/photographers?

I would pass on the advice I got. And I would add that embracing the unexpected, taking risks and not being afraid to make mistakes has often led to breakthroughs and new directions for me. And last but not least, always find a way to make it fun – for yourself and, ideally, for others.

Any projects you are currently working on/future projects you can already share some details about?

To further explore and push the boundaries of the concept of digital publishing is a significant focus for me in relation to the medium of the book. At the same time, I feel the need to counterbalance the digital with something analog and expand both areas into each other, even into physical space.

I am keen on fostering exchange and collaborations, and I am actively involved in teaching and education. Another important aspect for me is engaging in conversations with colleagues and individuals from diverse professions who can offer fresh perspectives on questions of connectivity. I have a longstanding practice of connecting with women in the arts and education, and I am part of the Saloon Women’s Network, which has enriched my network and discussions on these topics.

Image credits: © Clara Bahlsen